The AI Hallucination Nightmare and a simple verification loop to make sure every reference actually exists

If there’s one thing keeping lawyers up at night about AI, it’s hallucinations. It scares the interns, paralegals, associates, partners, and even the judges. The moment when a model confidently spits out a case that doesn’t exist or a quote no judge ever wrote is simply a terror and makes us wonder whether AI is worth it at all. We’ve all seen the cautionary tales. The lawyers who mess up are not only sanctioned, but publicly shamed.

Hallucinations are real because of how large language models work. They generate plausible text, not verified facts. Even as the technology improves, the problem doesn’t disappear; it just shrinks. OpenAI’s system card for GPT‑5 reports hallucination rates 65% lower than before. But fewer is not none. And a model with fewer errors does not relieve any attorney of the ethical requirements to verify citations.

Our ethical rules leave no ambiguity about who is responsible. ABA Formal Opinion 512 tells lawyers to consider competence, confidentiality, supervision, and review when using generative AI; that includes verifying outputs before relying on them. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11 independently requires that any paper a lawyer signs is grounded in existing law or a good‑faith argument for change—after a “reasonable inquiry.” If a model fabricates a cite and a lawyer doesn't catch it, that’s on them. Asking an AI “are these authorities real?” does not satisfy Rule 11 or the duty of candor to the tribunal.

Courts are also writing disclosure into their own local rules. A growing number of judges require parties to disclose whether and how generative AI was used and to certify that cited authority has been verified. The trend isn’t uniform at this point, but it is becoming more and more likely that an attorney not only must verify all citations and arguments, but also disclose whether or not AI was used in any way to research or prepare the filing.

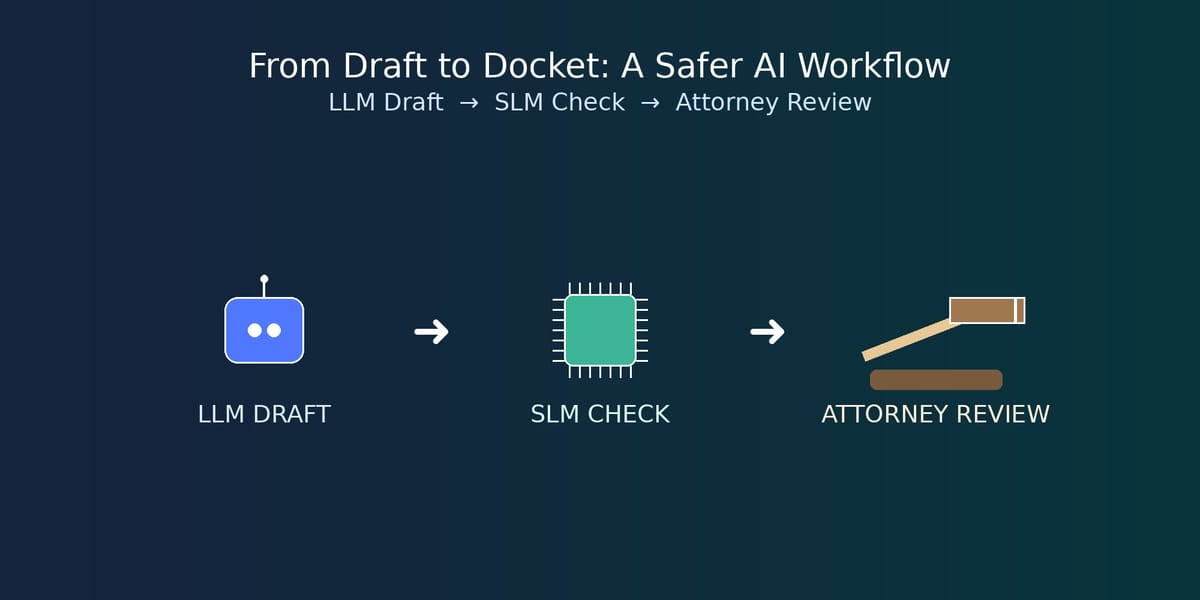

So how do you make hallucinations a manageable, not existential, risk in practice? Part of the answer is architectural. Don’t just “use an LLM.” Pair a strong LLM with a small language model (SLM) that acts as a fast, focused checker. The LLM can research and draft while the SLM can do targeted tasks like extracting every proposition of law and every citation, running structured checks, and flagging unsupported statements for a human to resolve. Think of the SLM as a tireless paralegal with a very short job description. Research backs the basic idea: retrieval‑augmented generation (RAG) and verification pipelines—where a model is grounded in retrieved sources and a separate component checks claims—reduce hallucinations compared to “just ask the model,” including in the legal domain. They don’t eliminate risk, but they bend it downward in a way you can supervise and document.

In practical terms, that looks like this in a firm workflow. Use the LLM to draft a research memo or a first‑cut brief section. Have your SLM pass comb through the draft and produce a “claims and citations” worksheet—every legal proposition mapped to authority. For each citation, the SLM can attempt a lightweight check (e.g., does this case exist, does the quote appear) and tag anything ambiguous or mismatched. Then a lawyer verifies everything in a citator and the record, corrects the draft, and logs what was checked. If your judge requires AI disclosure or certification, you’ll already have an audit trail. If not, you still have a defensible process consistent with Rule 11 and ABA 512. This setup and training takes a little work up front, but it pays massive dividends on a daily basis.

The bottom line for law practice is straightforward. Treat an LLM like a powerful junior who writes fast and needs supervision. Use newer models to reduce baseline error rates, but build a belt‑and‑suspenders workflow that separates drafting from checking. Consider an SLM+LLM setup with retrieval and verification so you can scale good habits, not just speed. A single tool’s confidence cannot substitute for a lawyer's verification.